Earthworms at Fordhall

December 18, 2025

Through their natural activities of burrowing and feeding, earthworms give rise to soils with many positive attributes.

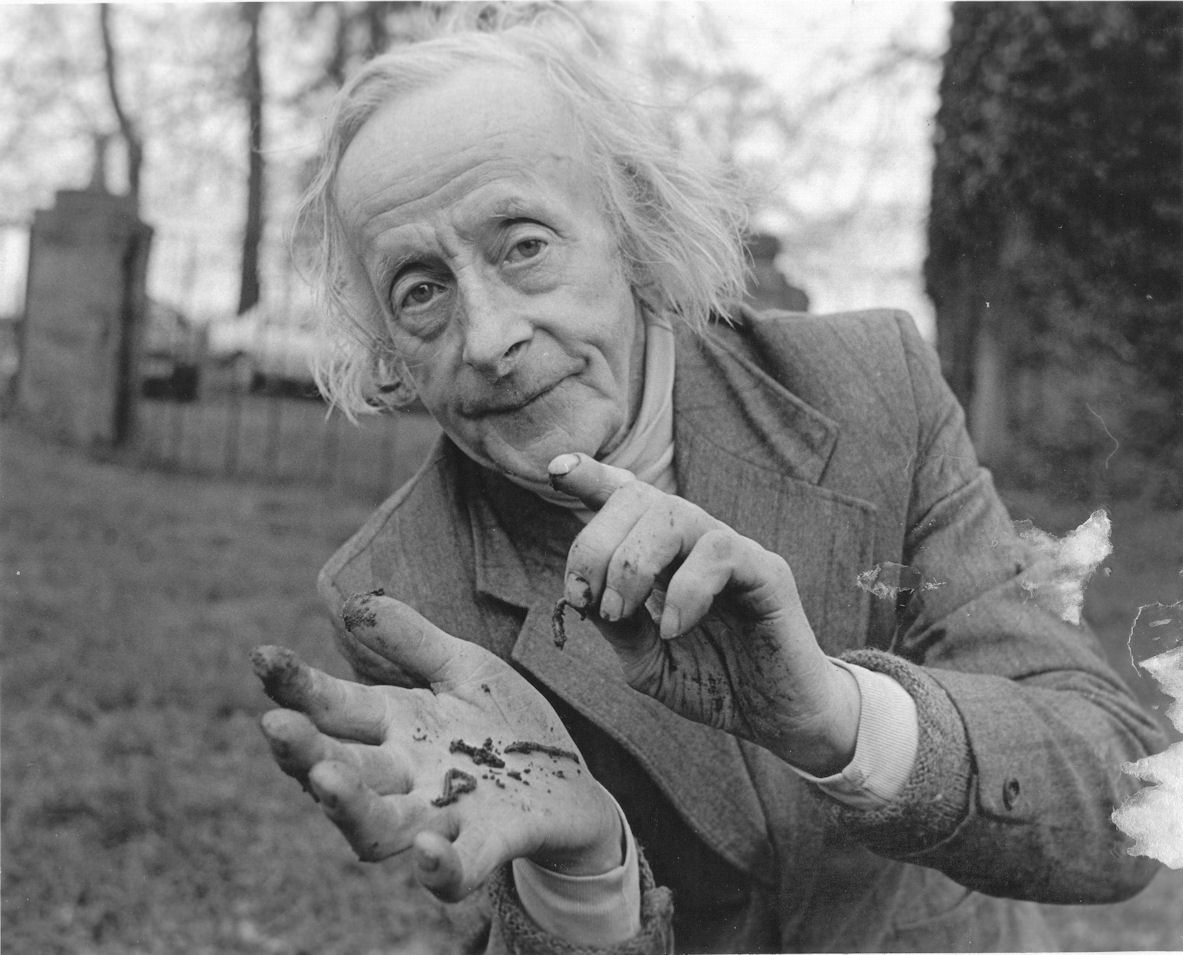

We were very excited to welcome worm experts, Dr Kevin Butt and Dr Pia Euteneuer, for a foray into the world earthworms at Fordhall Organic Farm. The public joined these experts for a fully lead session, learning all about the worms on-site.

Earthworms are essential for soil health, improving soil structure, drainage, and nutrient cycling. Fordhall’s foggage farming system, an outdoor-grazing, permaculture system pioneered by Arthur Hollins, works with nature and values the contribution and the necessity of these soil-dwelling creatures. Read Dr Kevin Butt's report on the workers in our soil...

They contribute to the maintenance of soil functions and biodiversity and provide numerous ecosystem services (ways that we gain from the natural world). These services include soil formation (pedogenesis) and the development of soil structure, by production of castings which amalgamate organic and inorganic components, forming a good base for plant growth. By feeding on and gaining their nutrition from the organic fraction of soil, earthworms greatly contribute to the cycling of nutrients and, in combination with microorganisms, make them more available to plants. Soil water is regulated by infiltration through earthworm burrows and prevents surface runoff that can lead to soil erosion. The burrows also allow air to enter the soil and provide oxygen for other organisms that are involved in soil processes. On a broader scale, earthworms are also concerned with climate regulation and pollution remediation and are a significant element in food webs.

The presence of earthworms in most temperate soils is therefore seen as essential. In agricultural soils, traditional techniques of soil tillage and chemical use may severely reduce earthworm numbers, but under organic farming, earthworm numbers will benefit from the practices undertaken and numbers in pasture are likely to be high.

In March 2025, a preliminary investigation was undertaken of the earthworms at Fordhall Organic Farm. This site was chosen as it has been under organic agricultural practices and chemical-free for over seventy years. The aim was to learn as much as possible of the earthworms present from selected areas of interest. Specific objectives were to determine abundance (how many earthworms), biomass (living weight of earthworms), ecological groupings, and species of earthworms present.

After a walk over the farm estate with Charlotte Hollins (General Manager of the Fordhall Community Land Initiative), three locations (House Field; Broad Meadow; Banky Field) were selected for sampling. These sites were chosen due to differences in soil type and elevation, plus current management, such as level of stocking density.

Earthworms were collected by digging and hand-sorting of soil, followed by addition of an earthworm expellant. Three quadrats of 0.1m-2 were randomly located within each field. Each was dug to 20cm depth and the soil sorted for earthworm presence on plastic sheeting. All animals were collected alive into small plastic pots containing fresh water. A suspension of mustard powder (5g L-1 of water) was used as an expellant and poured into the hole created by soil removal. This was to collect any deep burrowing species which would take evasive action when the hole was dug. (The mustard irritates their skin and they emerge to escape it.) Any earthworms emerging from deeper burrows were washed with water and then added to those collected by hand-sorting of soil. The earthworms were then examined in the field and subdivided by species, ecological group and by stage of development, weighed with a portable balance and released. The three ecological groupings of earthworms relate mainly to their burrowing behaviour: - litter dwelling (epigeic) live above the mineral soil in organic matter; shallow burrowing (endogeic) have non-permanent burrows within the upper 20cm of the soil; and deep burrowing (anecic) earthworms may have a permanent vertical burrow to 1m or deeper.

In addition to researcher-focused earthworm collection, members of the public were encouraged to assist as citizen scientists. More than a dozen people came along to the farm and learned something of earthworm science as they assisted in a “Get wormy with experts” event.

Overall, eight earthworm species were identified from systematic sampling. The shallow burrowing species were Allolobophora chlorotica (the green worm), Aporrectodea caliginosa (the grey worm), Aporrectodea rosea (the rosy-tipped worm) and Octolasion cyaneum (the steel-blue worm). Deep burrowing species consisted of Aporrectodea longa (the black-headed worm) and Lumbricus terrestris (the lob worm). Two litter dwelling species, Lumbricus rubellus (the red worm) and Satchellius mammalis (the little tree worm) were also found.

Numbers and masses of earthworms in the soil are a good indication of soil quality and health. From several studies, it has been recorded that pasture in Britain might produce an abundance of 390-525 ind. m-2 with a biomass of 52-200 g m-2. Results from the current investigation show that Banky Field is within this range, Broad Meadow a little below and House Field well above, although it has been shown that permanent pasture in New Zealand can hold over 1,000 earthworms m-2. These numbers are certainly a function of soil quality (e.g., texture, organic matter content), history of land use and current management. Low-lying Broad Meadow, close to the River Tern, was observed to be ‘patchy’ in earthworm abundance, as some areas were waterlogged, and one sample (of three examined) appeared to have anaerobic conditions in the soil and produced zero earthworms. By contrast the other two fields, higher on a ridge, appeared more freely draining. Management of Banky field with heavy grazing over the winter may have had a negative effect on earthworms due to the direct poaching of the soil, although this could be offset by a direct application of dung.

In both House Field and Broad Meadow, shallow working species dominated by number with the larger deep burrowing species accounting for the majority of earthworm biomass. However, this was not the case in Banky Field where shallow working species were more numerous and contributed most to earthworm mass. A relatively small number of litter dwelling species was expected from sampling, as pasture does not provide the large amount of leaf litter that these species normally require. Nevertheless, provision of dung has a similar function and may lead to patchy distribution of litter dwelling species when present, as shown for S. mammal is, found only below dung in Banky Field. The most numerous species overall was A. caliginosa (the grey worm) which is commonly found in pasture and is the most recorded earthworm across Britain and in many agricultural systems.

These results at Fordhall Organic Farm show that, from the three pastures sampled, earthworm numbers and biomasses were in good order and are a function of soil conditions. It is likely that further investigations of other fields, within selected non-pasture habitats such as woodland, riverside and around buildings, would undoubtedly reveal further earthworm species at Fordhall Organic Farm. Future, more detailed earthworm-related research would sensibly seek to answer specific questions. These might usefully draw comparisons between fields, where known differences exist. Such differences could be due to soil type, elevation, management and even time since organic practices were instigated, as appropriate.

Dr. Kevin Butt, Reader in Ecology, University of Central Lancashire